Combining data and design to shed light on Little Syria, a forgotten NYC ethnic enclave.

![]()

Timeline: October 2021 – November 2021

Tools: Google Data Studio, Tableau, Adobe Illustrator

Skills: Historic research -> data cleaning -> data analysis -> data visualization -> information design

So, what’s Little Syria?

In 2019, I took part in a walking tour of Little Syria, a neighborhood located in modern-day Tribeca and The Financial District. Having spent many years of my life on Manhattan's Lower West Side, I was shocked to learn of the existence of a former Arab enclave razed for the construction of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, adjacent to the World Trade Center complex.

![]()

From 1880-1924, The United States experienced its first wave of mass immigration. During these four decades, more than 95,000 Arabs emigrated from their native countries in search of economic opportunities and in hopes of beginning new lives. Although Arab Americans were an integral part of the Lower West Side’s history, Arab American culture is often either misunderstood or overlooked. Many New Yorkers who frequent Manhattan’s Lower West Side are not aware of the existence of the former Little Syria.

![]()

Today, of the over 3.7 million Arab Americans living in the United States, most are no longer immigrants but are native-born. With anti-Arab sentiments growing in the United States, and an increase in racial profiling and bias against Arab-Americans, we should strive to counteract prejudice and to learn more about this group of Americans and their cultures as well as about the past history of currently gentrifying neighborhoods.

Research, ideation, and iteration

The early 1900s represented the prime of Little Syria, as the neighborhood began to decline in the 1940s due to eminent domain and the construction of Robert Moses’ historic Brooklyn Battery Tunnel. This structure mitigated concerns over increasing traffic on the Williamsburg, Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges, but displaced over over 1,500 residents within the former Arab-American enclave.

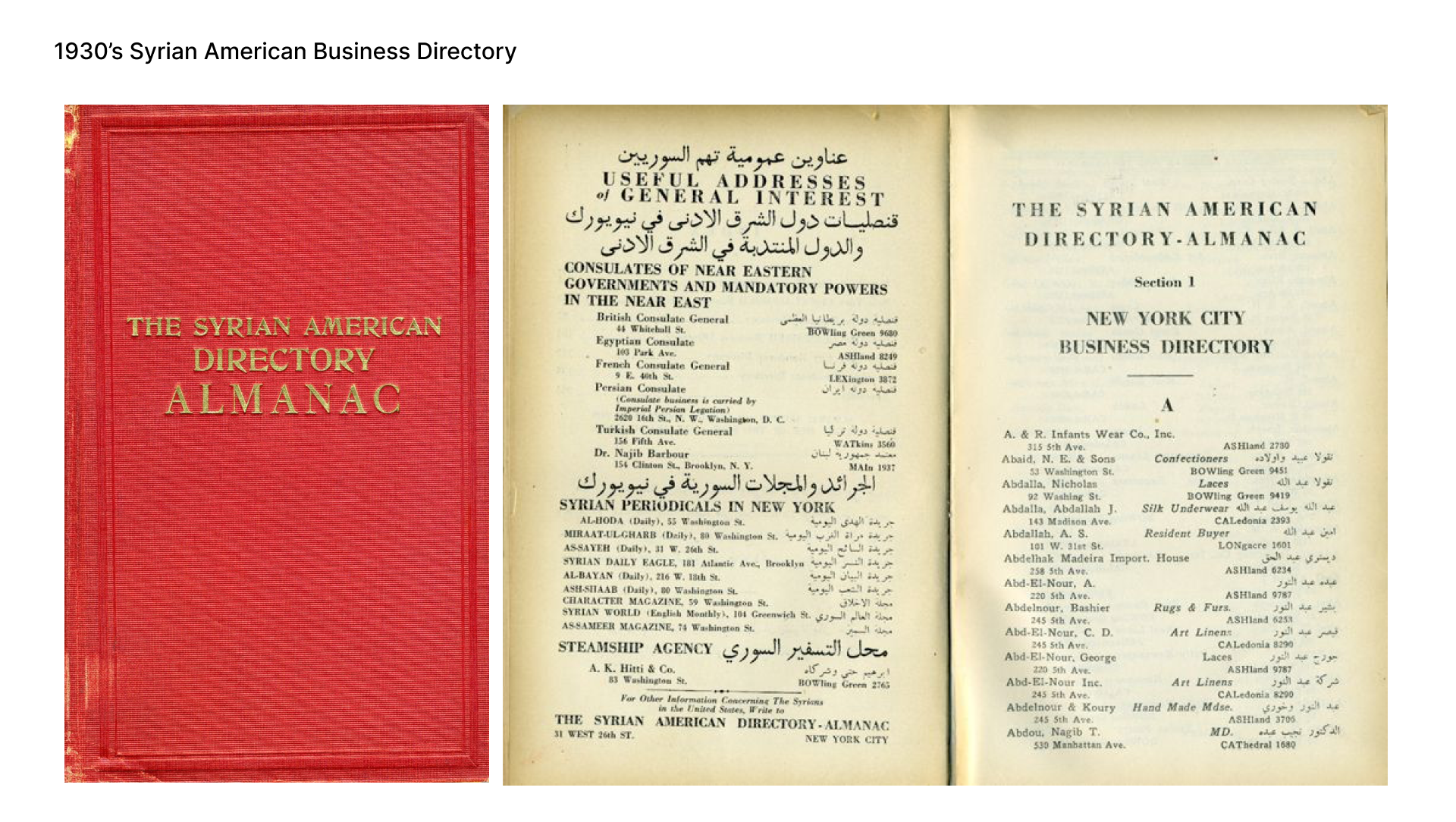

Little Syria thrived at a time before ZIP codes were introduced in 1963. Upon digging into historic archives, it was difficult to obtain census information based on geographic location. So as to better understand Little Syria at the height of its success, I uncovered a 1930’s Syrian American directory and used text extraction software to digitize the records for all businesses within the borough of Manhattan.

![]()

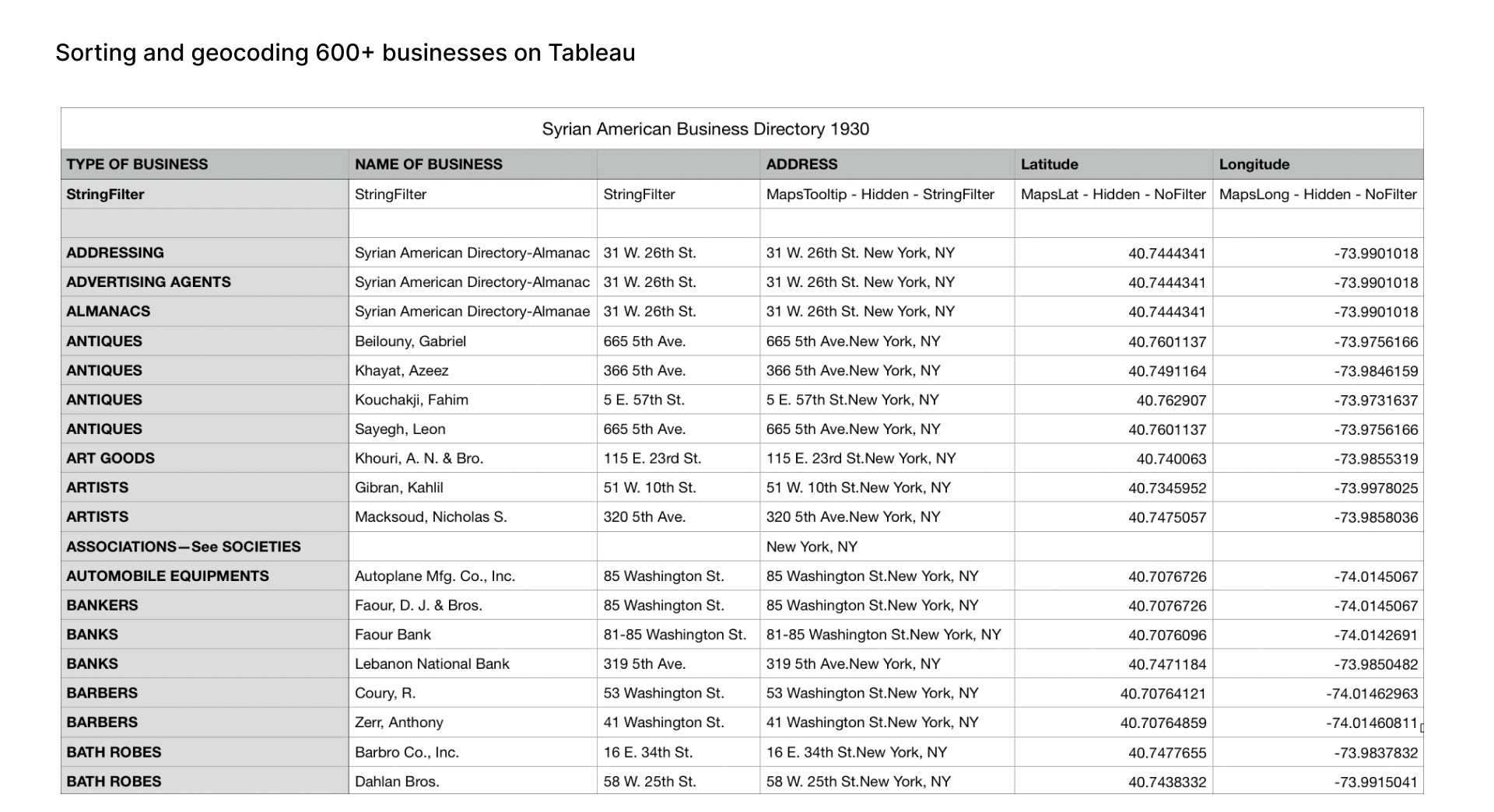

I geocoded over 600+ addresses, transported the data into Tableau, filtered the entries by business type, and isolated the businesses within the boundaries of the former neighborhood. I manually fixed any errors including invalid geocodes, and after 7+ iterations of error detection and correction within the dataset, I was left with over 174 businesses within the boundaries of former Little Syria.

![]()

![]()

![]()

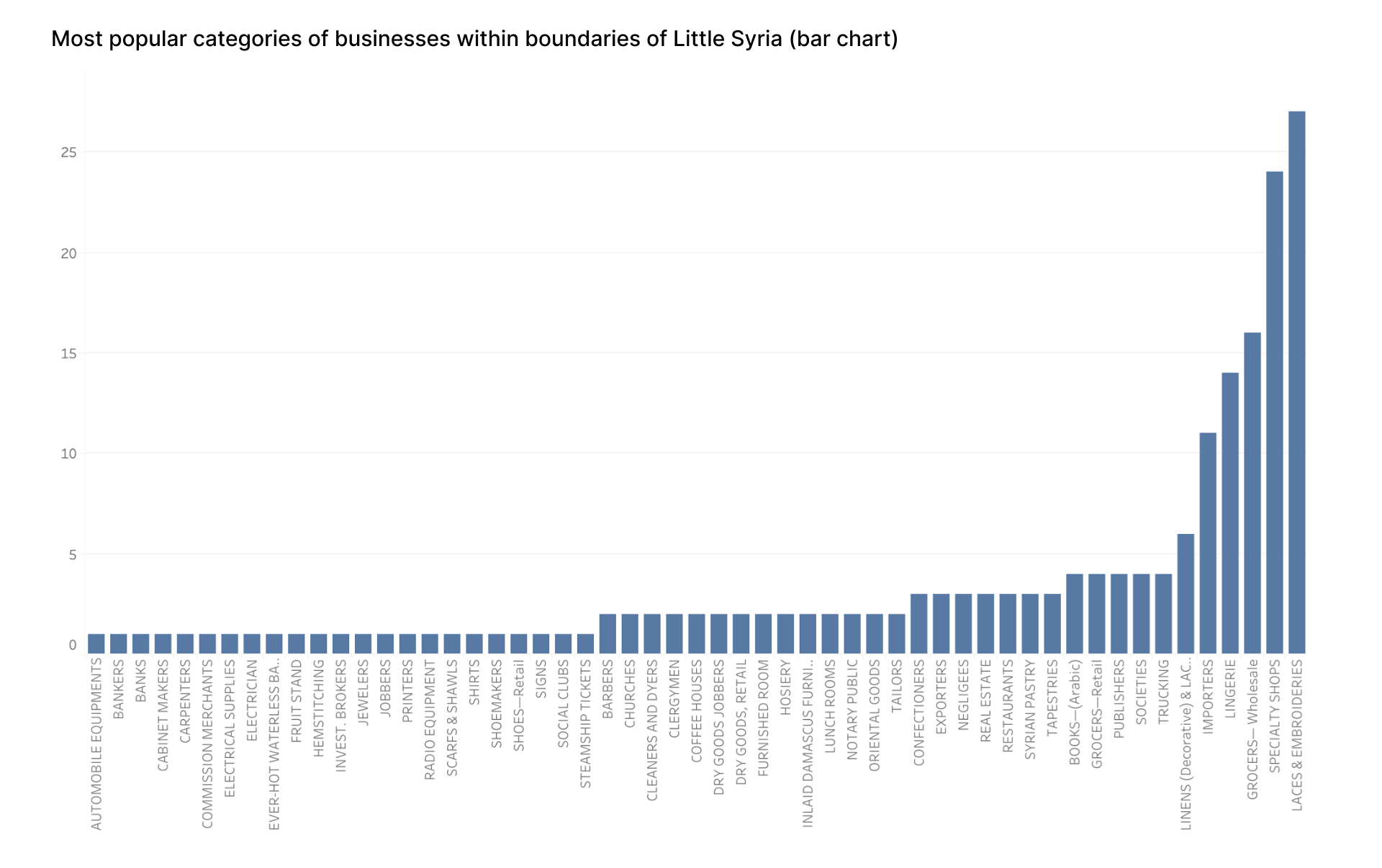

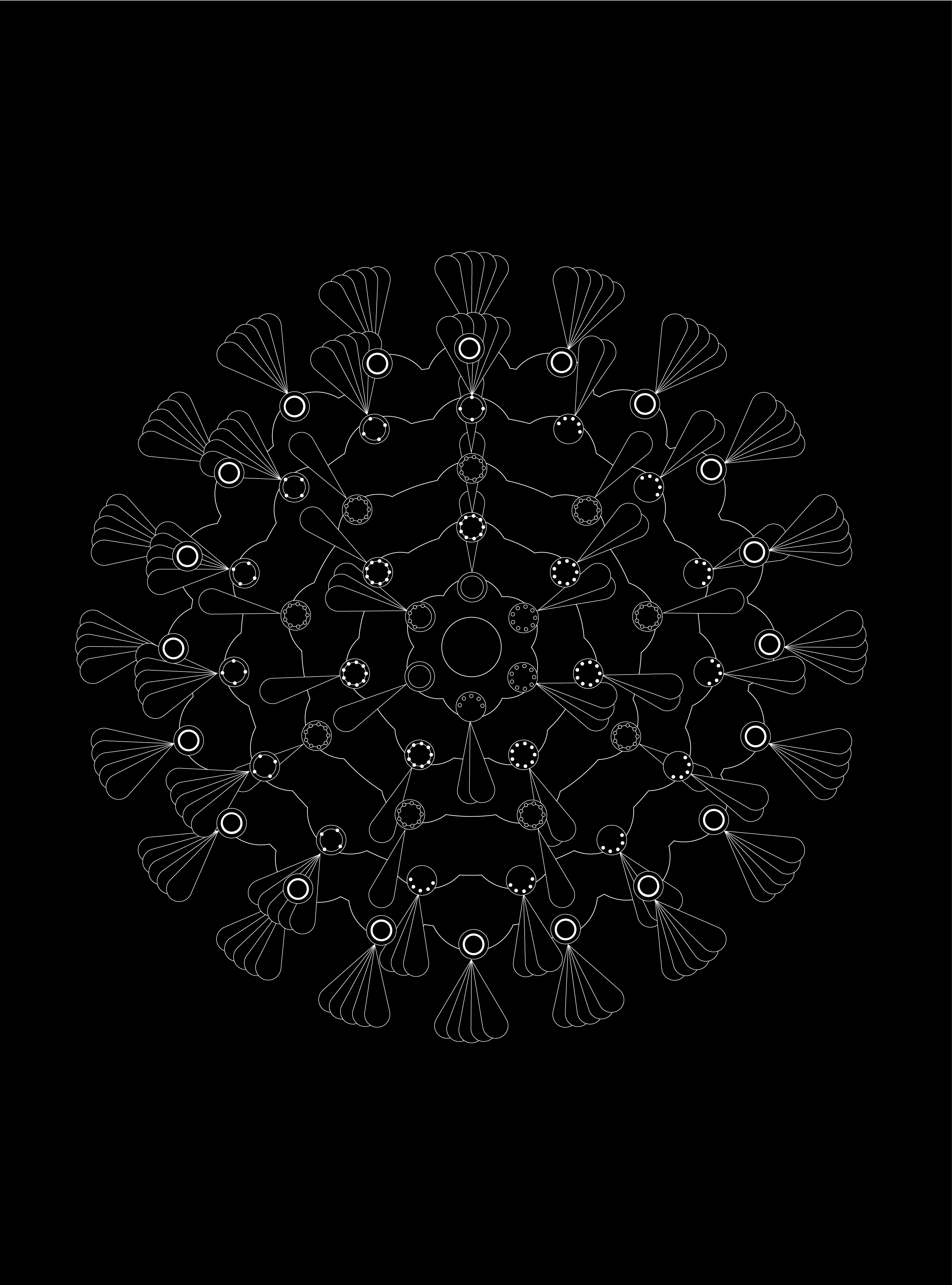

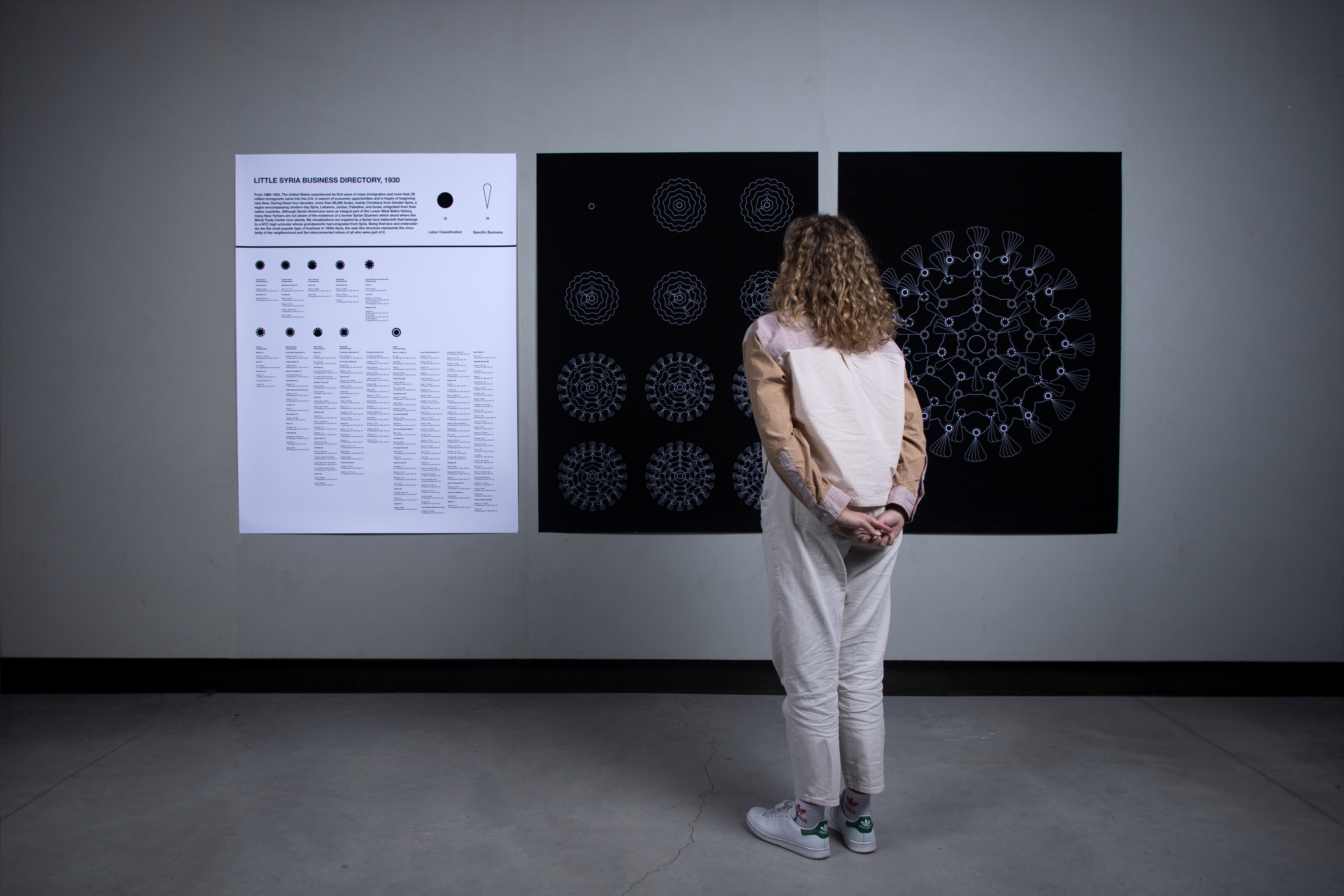

Data reveals that Little Syria was a vibrant, self-sustaining neighborhood filled with diverse industry. My visualizations are inspired by a Syrian lace tablecloth, one exhibited by New York Historical Society and was brought over from Syria in the late 1920s. Since lace and embroideries were the most popular type of business in 1930’s Little Syria, the lace-like web represents the circularity of the neighborhood and the interconnected nature of all who were part of it.

![]()

When you walk on the Lower West Side today, you see a quickly gentrifying neighborhood lined with skyscrapers. While I could’ve easily created visualizations using automated mapping software, I chose to create these visualizations on Adobe Illustrator, using more analog means, to pay homage to Arab lace-making traditions.

![]()

The final visualizations

The 174 total businesses within Little Syria, in the 1930’s directory, were classified into over 50 general categories. I then split the businesses into 10 distinct industries based on the North American Industry Classification System. Each distinct circular pattern represents a different industry, and each motif is a single business. By adding on one industry at a time, I figuratively construct the fabric of the neighborhood through information design.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

// Lace and embroidaries, as crafts, require percision and attention to detail. But often, the analog nature of the crafts may lead to unintentional errors. I am aware of the inevitability of human error and of possible impurities within my dataset, but the purpose of this project is to shed light on remnants of New York City history, not for complete data accuracy.

// Want to learn more? Check out A platform to help New Yorkers visualize local history through immersive digital exhibitions.

Tools: Google Data Studio, Tableau, Adobe Illustrator

Skills: Historic research -> data cleaning -> data analysis -> data visualization -> information design

So, what’s Little Syria?

In 2019, I took part in a walking tour of Little Syria, a neighborhood located in modern-day Tribeca and The Financial District. Having spent many years of my life on Manhattan's Lower West Side, I was shocked to learn of the existence of a former Arab enclave razed for the construction of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, adjacent to the World Trade Center complex.

From 1880-1924, The United States experienced its first wave of mass immigration. During these four decades, more than 95,000 Arabs emigrated from their native countries in search of economic opportunities and in hopes of beginning new lives. Although Arab Americans were an integral part of the Lower West Side’s history, Arab American culture is often either misunderstood or overlooked. Many New Yorkers who frequent Manhattan’s Lower West Side are not aware of the existence of the former Little Syria.

Today, of the over 3.7 million Arab Americans living in the United States, most are no longer immigrants but are native-born. With anti-Arab sentiments growing in the United States, and an increase in racial profiling and bias against Arab-Americans, we should strive to counteract prejudice and to learn more about this group of Americans and their cultures as well as about the past history of currently gentrifying neighborhoods.

Research, ideation, and iteration

The early 1900s represented the prime of Little Syria, as the neighborhood began to decline in the 1940s due to eminent domain and the construction of Robert Moses’ historic Brooklyn Battery Tunnel. This structure mitigated concerns over increasing traffic on the Williamsburg, Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges, but displaced over over 1,500 residents within the former Arab-American enclave.

Little Syria thrived at a time before ZIP codes were introduced in 1963. Upon digging into historic archives, it was difficult to obtain census information based on geographic location. So as to better understand Little Syria at the height of its success, I uncovered a 1930’s Syrian American directory and used text extraction software to digitize the records for all businesses within the borough of Manhattan.

I geocoded over 600+ addresses, transported the data into Tableau, filtered the entries by business type, and isolated the businesses within the boundaries of the former neighborhood. I manually fixed any errors including invalid geocodes, and after 7+ iterations of error detection and correction within the dataset, I was left with over 174 businesses within the boundaries of former Little Syria.

Data reveals that Little Syria was a vibrant, self-sustaining neighborhood filled with diverse industry. My visualizations are inspired by a Syrian lace tablecloth, one exhibited by New York Historical Society and was brought over from Syria in the late 1920s. Since lace and embroideries were the most popular type of business in 1930’s Little Syria, the lace-like web represents the circularity of the neighborhood and the interconnected nature of all who were part of it.

When you walk on the Lower West Side today, you see a quickly gentrifying neighborhood lined with skyscrapers. While I could’ve easily created visualizations using automated mapping software, I chose to create these visualizations on Adobe Illustrator, using more analog means, to pay homage to Arab lace-making traditions.

The final visualizations

The 174 total businesses within Little Syria, in the 1930’s directory, were classified into over 50 general categories. I then split the businesses into 10 distinct industries based on the North American Industry Classification System. Each distinct circular pattern represents a different industry, and each motif is a single business. By adding on one industry at a time, I figuratively construct the fabric of the neighborhood through information design.

// Lace and embroidaries, as crafts, require percision and attention to detail. But often, the analog nature of the crafts may lead to unintentional errors. I am aware of the inevitability of human error and of possible impurities within my dataset, but the purpose of this project is to shed light on remnants of New York City history, not for complete data accuracy.

// Want to learn more? Check out A platform to help New Yorkers visualize local history through immersive digital exhibitions.